what name was given to white southerners who supported radical reconstruction

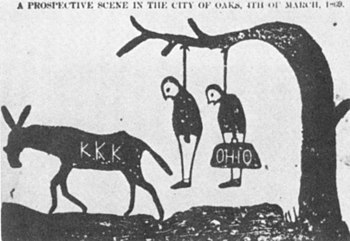

A Sept. 1868 cartoon in Alabama's Independent Monitor, threatening that the KKK would lynch scalawags (left) and carpetbaggers (right) on March 4, 1869, predicted every bit the first day of Democrat Horatio Seymour's presidency (the election winner was actually Ulysses Southward. Grant).

In Us history, the term scalawag (sometimes spelled scallawag or scallywag) referred to white Southerners who supported Reconstruction policies and efforts after the conclusion of the American Ceremonious War.

Every bit with the term carpetbagger, the word has a long history of use as a slur in Southern partisan debates. The post-Civil War opponents of the scalawags claimed they were disloyal to traditional values and white supremacy.[1] Scalawags were peculiarly hated by 1860s-1870s Southern Democrats, who chosen Scalawags traitors to their region (long known for its widespread chattel slavery). Prior to the Civil War, near Scalawags had been opposed to the southern states' (the Confederacy'due south) secession from the USA.[2]

The term is commonly used in historical studies as a descriptor of modern Southern white Republicans, although some historians have discarded the term due to its history of pejorative connotations.[3]

Origins of the term [edit]

The term is a derogatory epithet, yet it is used past many historians anyway, as in Wiggins (1991), Baggett (2003),[4] Rubin (2006), and Wetta (2012). The discussion scalawag has an uncertain origin. Its primeval attestation is from 1848 to mean a disreputable beau,[v] adept-for-nothing, scapegrace, or blackguard.[ citation needed ] It has been speculated that "perhaps the original use of the give-and-take" referred to low-class farm animals, merely this meaning of the word is non attested until 1854.[6] The term was later adopted by their opponents to refer to Southern whites who formed a Republican coalition with black freedmen and Northern newcomers (called carpetbaggers) to accept control of their country and local governments.[ citation needed ] Among the earliest uses in this new significant were references in Alabama and Georgia newspapers in the summer of 1867, beginning referring to all Southern Republicans, then later restricting it to only white ones.[i]

Historian Ted Tunnel writes that

Reference works such as Joseph Emerson Worcester's 1860 Lexicon of the Caribbean Spanish Linguistic communication defined scalawag equally "A depression worthless fellow; a scapegrace." Scalawag was also a word for low-grade farm animals. In early on 1868 a Mississippi editor observed that scalawag "has been used from time immemorial to designate inferior milch cows in the cattle markets of Virginia and Kentucky." That June the Richmond Enquirer concurred; scalawag had heretofore "applied to all of the mean, lean, mangy, hidebound skiny [sic], worthless cattle in every particular drove." Only in recent months, the Richmond paper remarked, had the term taken on political meaning.

During the 1868–69 session of Judge "Greasy" Sam Watts' court in Haywood Canton, North Carolina, William Closs testified that a scalawag was "a Native built-in Southern white man who says he is no improve than a negro and tells the truth when he says it". Some accounts record his testimony equally "a native Southern white man, who says that a negro is as good every bit he is, and tells the truth when he says so".

Past October 1868 a Mississippi newspaper was defining the expression scathingly in terms of Redemption politics.[vii] The term continued to be used equally a pejorative by conservative pro-segregationist southerners well into the 20th century.[8] But historians commonly use the term to refer to the group of historical actors with no debasing meaning intended.[9]

History [edit]

After the American Civil War during the Reconstruction Era 1863 to 1869, Presidents Abraham Lincoln and Andrew Johnson undertook policies designed to bring the Due south back to normal equally presently every bit possible, while the Radical Republicans used Congress to block the president, impose harsh terms, and upgrade the rights of the Freedmen (the ex-slaves). In the South, Black Freedmen and White Southerners with Republican sympathies joined forces with Northerners who had moved south (called "Carpetbaggers" by their southern opponents) to implement the policies of the Republican party.

Despite being a minority, scalawags gained power by taking advantage of the Reconstruction laws of 1867, which disenfranchised the majority of Southern white voters as they could not have the Ironclad oath, which required they had never served in Confederate armed forces or held whatsoever political office under the state or Confederate governments. Historian Harold Hyman says that in 1866 Congressmen "described the oath equally the last barrier against the return of ex-rebels to power, the barrier behind which Southern Unionists and Negroes protected themselves."[10]

The coalition controlled every old Confederate state except Virginia, as well every bit Kentucky and Missouri (which were claimed past the Northward and the Southward) for varying lengths of time betwixt 1866 and 1877. 2 of the about prominent scalawags were Full general James Longstreet, one of Robert E. Lee's meridian generals, and Joseph E. Chocolate-brown, who had been the wartime governor of Georgia. During the 1870s, many scalawags left the Republican Political party and joined the conservative-Democrat coalition. Conservative Democrats had replaced all Republican minority governments in the S by 1877, subsequently the disputed presidential ballot of 1876, in which the remaining Reconstruction governments had certified the Republican electors despite the Autonomous candidate having carried united states of america.

Historian John Hope Franklin gives an assessment of the motives of Southern Unionists. He noted that as more than Southerners were immune to vote and participate:[xi]

A curious assortment of native Southerners thus became eligible to participate in Radical Reconstruction. And the number increased as the President granted individual pardons or issued new proclamations of immunity ... Their master involvement was in supporting a party that would build the South on a broader base than the plantation aristocracy of Antebellum days. They plant it expedient to practice business with Negroes and so-chosen carpetbaggers, but often they returned to the Democratic party equally information technology gained sufficient strength to be a factor in Southern politics.

Somewhen most scalawags joined the Democratic Redeemer coalition. A minority persisted equally Republicans and formed the "tan" half of the "Black and Tan" Republican party. It was a minority element in the GOP in every Southern state after 1877.[12]

Most of the 430 Republican newspapers in the S were edited by scalawags—only twenty percent were edited by carpetbaggers. White businessmen by and large boycotted Republican papers, which survived through government patronage.[13] [14]

Alabama [edit]

In Alabama, Wiggins says scalawags dominated the Republican Political party. Some 117 Republicans were nominated, elected, or appointed to the nigh lucrative and of import land executive positions, judgeships, and federal legislative and judicial offices between 1868 and 1881. They included 76 white southerners, 35 northerners, and 6 former slaves. In country offices during Reconstruction, white southerners were fifty-fifty more than predominant: 51 won nominations, compared to 11 carpetbaggers and i black. 27 scalawags won country executive nominations (75%), 24 won land judicial nominations (89%), and 101 were elected to the Alabama General Associates (39%). However, fewer scalawags won nominations to federal offices: 15 were nominated or elected to Congress (48%) compared to 11 carpetbaggers and 5 blacks. 48 scalawags were members of the 1867 constitutional convention (49.5% of the Republican membership); and seven scalawags were members of the 1875 ramble convention (58% of the minuscule Republican membership.)[15]

In terms of racial issues, Wiggins says:

White Republicans equally well as Democrats solicited blackness votes but reluctantly rewarded blacks with nominations for role but when necessary, fifty-fifty then reserving the more choice positions for whites. The results were anticipated: these half-a-loaf gestures satisfied neither blackness nor white Republicans. The fatal weakness of the Republican party in Alabama, as elsewhere in the Due south, was its inability to create a biracial political political party. And while in power even briefly, they failed to protect their members from Autonomous terror. Alabama Republicans were forever on the defensive, verbally and physically."[sixteen]

Due south Carolina [edit]

In South Carolina in that location were virtually 100,000 scalawags, or about xv% of the white population. During its heyday, the Republican coalition attracted some wealthier white southerners, especially moderates favoring cooperation betwixt open-minded Democrats and responsible Republicans. Rubin shows that the plummet of the Republican coalition came from disturbing trends to corruption and factionalism that increasingly characterized the party'due south governance. These failings disappointed Northern allies who abandoned the state Republicans in 1876 as the Democrats nether Wade Hampton reasserted command. They used the threat of violence to cause many Republicans to stay quiet or switch to the Democrats.[17]

Louisiana [edit]

Wetta shows that New Orleans was a major Scalawag heart. Their leaders were well-to-practice well-educated lawyers, physicians, teachers, ministers, businessmen, and civil servants. Many had Northern ties or were born in the North, moving to the boom city of New Orleans before the 1850s. Few were cotton or sugar planters. Nigh had been Whigs before the State of war, but many had been Democrats. Well-nigh all were Unionists during the War. They had joined a Republican coalition with blacks but gave at best weak back up to black suffrage, black office holding, or social equality. Wetta says that their "cosmopolitanism bankrupt the mold of southern provincialism" typical of their southern-democratic opponents. That is, scalawags had "a broader worldview."[18]

Mississippi [edit]

The virtually prominent scalawag of all was James Fifty. Alcorn of Mississippi. He was elected to the U.South. Senate in 1865, just like all southerners was not allowed to have a seat while the Republican Congress was pondering Reconstruction. He supported suffrage for freedmen and endorsed the Fourteenth Amendment, as demanded past the Republicans in Congress. Alcorn became the leader of the scalawags, who composed most a third of the Republicans in the state, in coalition with carpetbaggers and freedmen. Elected governor past the Republicans in 1869, he served from 1870 to 1871. Every bit a modernizer he appointed many like-minded former Whigs, even if they were Democrats. He strongly supported education, including public schools for blacks merely, and a new college for them, at present known as Alcorn Country Academy. He maneuvered to make his ally Hiram Revels its president. Radical Republicans opposed Alcorn and were aroused at his patronage policy. One complained that Alcorn's policy was to see "the old civilisation of the Due south modernized" rather than lead a total political, social and economic revolution.[19]

Alcorn resigned the governorship to become a U.S. Senator (1871–1877), replacing his marry Hiram Revels, the first African American senator. Senator Alcorn urged the removal of the political disabilities of white southerners, rejected Radical Republican proposals to enforce social equality by federal legislation, he denounced the federal cotton tax as robbery and dedicated divide schools for both races in Mississippi. Although a former slaveholder, he characterized slavery as a cancer upon the body of the Nation and expressed the gratification which he and many other Southerners felt over its destruction.[20]

Alcorn led a furious political battle with Senator Adelbert Ames, the carpetbagger who led the other faction of the Republican Party in Mississippi. The fight ripped autonomously the party, with most blacks supporting Ames, but many—including Revels, supporting Alcorn. In 1873, they both sought a decision by running for governor. Ames was supported by the Radicals and nearly African Americans, while Alcorn won the votes of bourgeois whites and nigh of the scalawags. Ames won by a vote of 69,870 to 50,490, and Alcorn retired from state politics.[21]

Newton Knight has gained increased attention since the 2016 release of the characteristic motion-picture show Free State of Jones.

Mountains [edit]

The mountain districts of Appalachia were oftentimes Republican enclaves.[22] People there held few slaves, and they had poor transportation, deep poverty, and a continuing resentment against the Low Country politicians who dominated the Confederacy and bourgeois Democrats in Reconstruction and afterward. Their strongholds in Due west Virginia, eastern Kentucky and Tennessee, western Virginia and North Carolina, and the Ozark region of northern Arkansas, became Republican bastions. These rural folk had a long-standing hostility toward the planter class. They harbored pro-Union sentiments during the war. Andrew Johnson was their representative leader. They welcomed Reconstruction and much of what the Radical Republicans in Congress advocated.[iv]

Outside the Us [edit]

The term 'scally' is as well used in the United Kingdom to refer to elements of the working form and fiddling criminality, in a like vein to the more than gimmicky chav. In Philippines, scalawags were used to denote rogue police or military officers.

Accusations of corruption [edit]

Scalawags were denounced as decadent by Redeemers. The Dunning School of historians sympathized with the claims of the Democrats. Agreeing with the Dunning School, Franklin said that the scalawags "must take at least office of the arraign" for graft and corruption.[23]

The Democrats alleged the scalawags to be financially and politically corrupt, and willing to back up bad authorities considering they profited personally. 1 Alabama historian claimed: "On economic matters scalawags and Democrats eagerly sought aid for economical development of projects in which they had an economic stake, and they exhibited few scruples in the methods used to push beneficial fiscal legislation through the Alabama legislature. The quality of the book keeping habits of both Republicans and Democrats was every bit notorious."[16] Nevertheless, historian Eric Foner argues in that location is not sufficient evidence that scalawags were any more or less corrupt than politicians of any era, including Redeemers.[24]

Who were the scalawags? [edit]

White Southern Republicans included formerly closeted Southern abolitionists equally well as former slaveowners who supported equal rights for freedmen. (The most famous of this latter group was Samuel F. Phillips, who later argued against segregation in Plessy v. Ferguson.) Included, too, were people who wanted to exist part of the ruling Republican Party but considering it provided more than opportunities for successful political careers. Many historians have described scalawags in terms of social grade, showing that on average they were less wealthy or prestigious than the aristocracy planter class.[four]

Equally Thomas Alexander (1961) showed, at that place was persistent Whiggery (support for the principles of the defunct Whig Party) in the South afterward 1865. Many ex-Whigs became Republicans who advocated modernization through didactics and infrastructure—especially better roads and railroads. Many also joined the Redeemers in their successful attempt to replace the brief period of civil rights promised to African Americans during the Reconstruction era with the Jim Crow era of segregation and 2d-class citizenship that persisted into the 20th century.

Historian James Alex Baggett's The Scalawags provides a quantitative study of the population.[four]

See also [edit]

| | Look upwards scalawag in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Southern Unionist

- Freedmen

- Peckerwood

- Reconstruction era of the United States

- Redeemers

- Collaborationism

- Pejorative

Notes [edit]

- ^ a b Ted Tunnell. 2006. Creating "The Propaganda of History": Southern Editors and the Origins of "Carpetbagger and Scalawag". The Journal of Southern History , Vol. 72, No. 4 (Nov., 2006), pp. 789–822

- ^ David Emory Shi, "American: A Narrative History Vol. 1 11th Edition." (2019): 753-54

- ^ Jack P. Maddex. 1980. More Facts of Reconstruction The Mean solar day of the Carpetbagger: Republican Reconstruction in Mississippi. past William C. Harris Jr. Reviews in American History, Vol. 8, No. 1 (Mar., 1980), pp. 69–73

- ^ a b c d Baggett, James Alex (September 2004). The Scalawags: Southern Dissenters in the Ceremonious War and Reconstruction. Billy Rouge, LA: LSU Press. ISBN9780807130148. Archived from the original on 13 April 2016. Retrieved 9 Jul 2016.

- ^ https://world wide web.etymonline.com/discussion/scalawag

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary p. 2655 (Meaty Edition). Oxford University Printing. 1974.

- ^ "A Mississippi newspaper gives this pointed description ... 'The carpet-bagger is a Northern thief who comes South to plunder every white man who is a admirer of any belongings or respectability, and get all the offices he can. The scalawag is a Southern-born scoundrel, who will do all the carpet-bagger will, and, as well, murder the carpeting-bagger for the gutta-percha ring his sister gave him when he left dwelling house.'" The Times, eight October 1868, p.9

- ^ Tucker, William H. (2002), The Funding of Scientific Racism: Wickliffe Draper and the Pioneer Fund, Academy of Illinois Press, ISBN 0-252-02762-0 p. 59

- ^ Richard D. Starnes. "Forever Faithful: The Southern Historical Society and Confederate Historical Memory". Southern Cultures, Volume two, Number 2, Winter 1996, pp. 177–194, note ii

- ^ Harold Hyman, To endeavor men's souls: loyalty tests in American history (1959) p 93

- ^ Franklin p. 100

- ^ DeSantis 1998

- ^ Stephen 50. Vaughn, ed., Encyclopedia of American journalism (2007) p 441.

- ^ Richard H. Abbott, For Free Press and Equal Rights: Republican Newspapers in the Reconstruction South (2004).

- ^ Wiggins 131–38

- ^ a b Wiggins p 134

- ^ Rubin 2006

- ^ Frank J. Wetta, The Louisiana Scalawags: Politics, Race, and Terrorism during the Ceremonious War and Reconstruction (Louisiana Land University Press, 2012) p 184

- ^ Quoted in Eric Foner, Reconstruction (1988) p 298.

- ^ Congressional Globe, 42 Cong., two Sess., pp. 246–47, 2730–33, 3424

- ^ Pereyra 1966

- ^ McKinney 1998

- ^ Franklin, p. 101

- ^ Foner, Reconstruction

References [edit]

- Alexander, Thomas B. (1961). "Persistent Whiggery in the Confederate South, 1860-1877". The Journal of Southern History. 27 (iii): 305–329. doi:10.2307/2205211. JSTOR 2205211.

- Baggett, James Alex (2003). The Scalawags: Southern Dissenters in the Civil War and Reconstruction. ISBN0-8071-2798-1.

- DeSantis, Vincent P. Republicans Face the Southern Question: The New Deviation Years, 1877–1897 (1998)

- Donald, David H. (1944). "The Scalawag in Mississippi Reconstruction". The Journal of Southern History. 10 (4): 447–460. doi:10.2307/2197797. JSTOR 2197797.

- Ellem, Warren A. (1972). "Who Were the Mississippi Scalawags?". The Journal of Southern History. 38 (ii): 217–240. doi:10.2307/2206442. JSTOR 2206442.

- Franklin, John Hope (1994). Reconstruction After the Civil State of war: Second Edition. ISBN0-226-26079-viii.

- Garner; James Wilford. Reconstruction in Mississippi (1901). online edition

- Ginsberg, Benjamin (2010). Moses of Due south Carolina: A Jewish Scalawag During Radical Reconstruction. Johns Hopkins U.P. ISBN9780801899164.

- Hume, Richard Fifty. and Jerry B. Gough. Blacks, Carpetbaggers, and Scalawags: The Ramble Conventions of Radical Reconstruction (Louisiana State University Press, 2008); statistical classification of delegates.

- Jenkins, Jeffery A., and Boris Heersink. "Republican Party Politics and the American Southward: From Reconstruction to Redemption, 1865-1880." (2016 newspaper t the 2016 Annual Coming together of the Southern Political Science Association); online.

- Kolchin, Peter (1979). "Scalawags, Carpetbaggers, and Reconstruction: A Quantitative Look at Southern Congressional Politics, 1868-1872". The Periodical of Southern History. 45 (1): 63–76. doi:x.2307/2207902. JSTOR 2207902.

- McKinney, Gordon B. Southern Mount Republicans, 1865–1900: Politics and the Appalachian Customs (1998)

- Pereyra, Lillian A., James Lusk Alcorn: Persistent Whig. (1966).

- Perman, Michael. The Route to Redemption: Southern Politics 1869–1879 (1984)

- Rubin, Hyman. South Carolina Scalawags (2006)

- Tunnell, Ted. "Creating 'the Propaganda of History': Southern Editors and the Origins of Carpetbagger and Scalawag," Periodical of Southern History (Nov 2006) 72#four online at The Gratis Library

- Wetta, Frank J. The Louisiana Scalawags: Politics, Race, and Terrorism During the Civil War and Reconstruction (Louisiana State University Press; 2012)

- Wiggins; Sarah Woolfolk. The Scalawag in Alabama Politics, 1865—1881 (1991)[ ISBN missing ]

Further reading [edit]

Principal sources [edit]

- Fleming, Walter 50. Documentary History of Reconstruction: Political, Armed forces, Social, Religious, Educational, and Industrial ii vol (1906). Uses broad drove of master sources; vol 1 on national politics; vol two on states

- Memoirs of W. W. Holden (1911), Northward Carolina Scalawag governor

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scalawag

0 Response to "what name was given to white southerners who supported radical reconstruction"

Post a Comment